07/10/2025

For as long as he can remember, Timothy Duerr ’17 has been fascinated with a scientific feature of salamanders. Not only can the amphibians regenerate their amputated limbs, but they know exactly what to grow back, regardless of whether they’ve lost a hand or an entire arm.

It’s a biological mystery that could one day spur human applications, and Duerr was part of the nine-person research team that recently published a breakthrough study about the process in Nature Communications, a highly regarded scientific journal.

The work already has earned the attention of National Geographic, CNN and Popular Science.

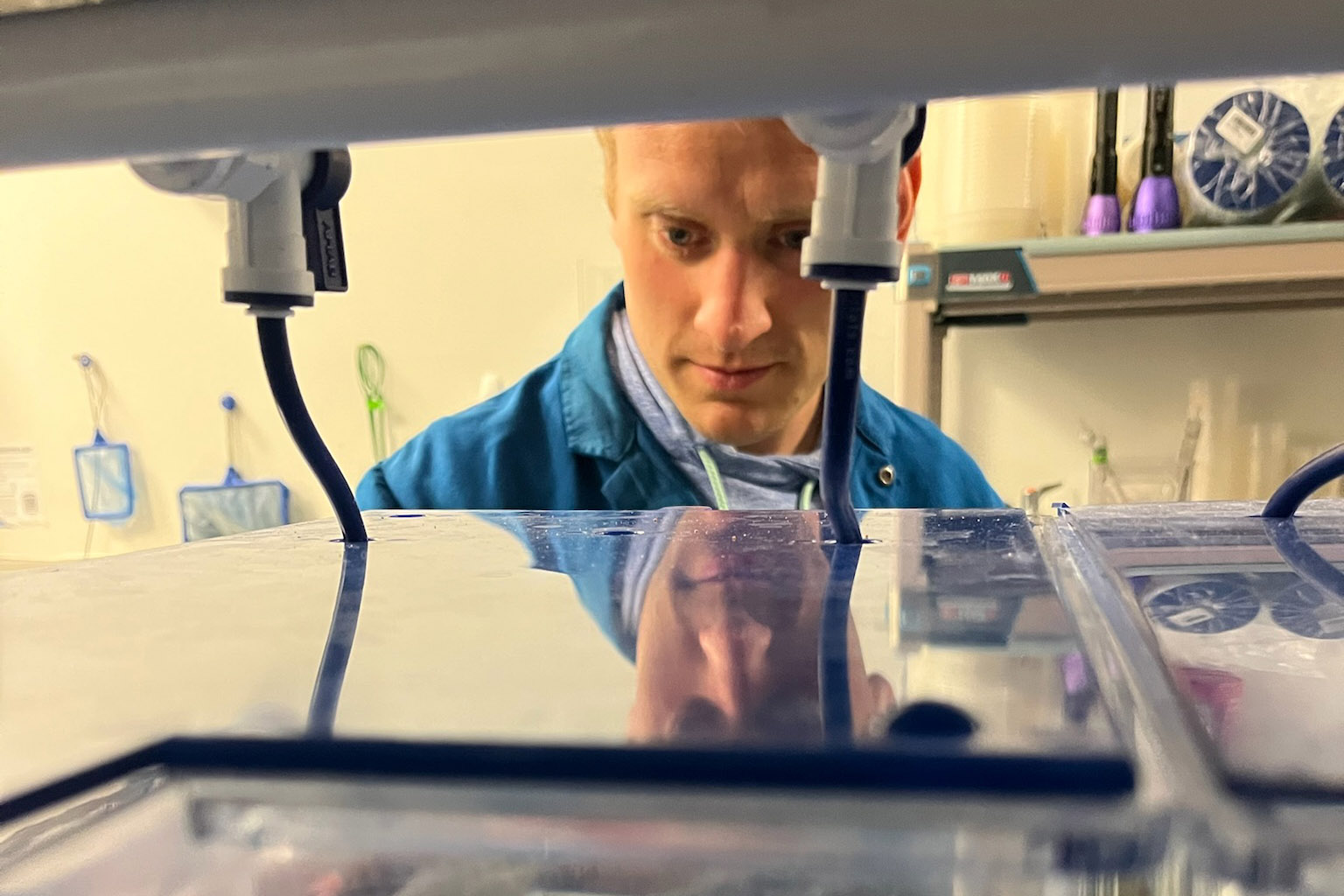

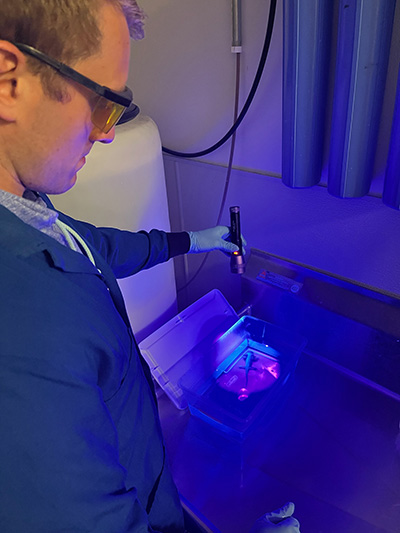

“Limb regeneration (in humans) is still a ways away, but I think we’ve definitely uncovered an important aspect of it,” said Duerr, a former high-achieving SUNY Cortland biology major who is now a research scientist in Northeastern University’s Institute for Chemical Imaging of Living Systems.

The recent journal article reflects more than five years of research in Duerr’s budding academic career. It’s also a piece of a much larger scientific puzzle. Questions about limb regeneration have motivated researchers for more than a century, according to SUNY Distinguished Teacher Professor of Biological Sciences Peter Ducey.

“Tim’s paper is one of many that are moving us forward,” said Ducey, who was Duerr’s academic advisor and research mentor during his undergraduate days. “But this question about how things regenerate has been a fundamental question in science for over a century. And his team, they are making some really important steps forward in this pursuit we’ve had as a society for a long time.”

At its core, the research paper dives deeper into the biological processes that allow axolotls — a type of salamander — to regrow exact missing limbs in the proper places.

Retinoic acid, which exists in humans and salamanders, has long been known to play an important role in the regeneration process. As Duerr explains it, when a salamander’s upper arm is amputated, the presence of retinoic acid helps regrow the full appendage. But when the salamander receives an amputation at the wrist, retinoic acid is absent as its hand reappears. So higher concentrations of retinoic acid result in an arm’s regrowth, while lower concentrations are responsible for a hand.

One of the recent publication’s key findings is that the concentration difference is controlled by an enzyme known as CYP26B1, which breaks down retinoic acid to ensure the salamander’s correct limb regrows. The enzyme also exists in humans.

“This is something that — at least mechanistically during regeneration — people haven’t seen before,” said Duerr, noting that the research team also uncovered a particular gene controlling skeleton growth in the upper arm.

That gene, known as Shox, existed at the salamander’s upper arm amputations but not at the wrist, suggesting that its activation also depends on retinoic acid concentration.

“We think this is a really interesting finding, not only in the context of limb regeneration, but with skeletal development in general,” Duerr said. “We would think that a phalanx (finger) would grow the same way as the humerus (in the arm). But what we’re seeing is that these bone growth programs might depend on very specific genes that are specific to the location of where they are in the body.

“So I think that’s a new frontier there that hasn’t been explored very much.”

Duerr started working on the project when he was a doctoral student at Northeastern. He was excited by the research potential and wanted to see it through to completion. So after earning his Ph.D. in biology in 2021, he opted for a postdoctoral position in the lab of James Monaghan, his advisor at Northeastern and the study’s lead author.

“Everything seemed to be coming together and telling a really cool story,” said Duerr, who has contributed to approximately 15 scientific papers to date. “I found it hard to leave that behind.”

That appreciation for “cool science,” a term that both Duerr and Ducey used, traces back to his time at SUNY Cortland. Ducey recalled Duerr’s innate curiosity about interesting scientific questions in classes and research labs. It’s a quality that has bonded the pair beyond graduation.

“Tim’s ability to understand the big ideas as well as the multitude of details was supplemented by his knack for solving problems as they arise,” said Ducey, suggesting that his former student’s aptitude was exceeded by his effort, humility and kindness. “We all could see that he was heading toward a very successful career in science.”

Duerr, who grew up in Massapequa, N.Y., began pursuing undergraduate research as a sophomore, and he embarked on a multiyear joint project that considered the evolutionary ecology of invasive flatworm species at the genetic level. The question originated in Ducey’s lab, then relied on molecular biology approaches and techniques in the lab of Patricia Conklin, professor emerita of biological sciences.

“It was awesome to be able to combine those experiences and work in both of those labs,” said Duerr, who earned several awards and distinctions at the university, from a perfect grade point average to the Biological Sciences Department’s Outstanding Achievement in Research Award.

The summer before his senior year, Duerr was one of just 20 students from across the country selected for a two-month undergraduate research experience at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He recalls Ducey encouraging him to apply for the opportunity during a visit to his office.

“I think that’s something so unique about Cortland, that I was able to develop such a close relationship with my professors, Dr. Ducey especially,” said Duerr, noting that he still consults his former advisor on pivotal decisions in his life and career. “I really think that (the Biological Sciences Department) is a true gem — really the entire STEM program in general. The professors were just absolutely amazing.”

When he began his pursuit of a Ph.D. in 2017, shortly after graduating from Cortland, Duerr said he felt well-prepared because his undergraduate experience taught him how to understand and digest scientific literature. Support from his wife, Emily, a middle school teacher of children who are deaf, has proven just as valuable in his young career.

Now, he’s the one producing ground-breaking research.

Ducey, who has taught at SUNY Cortland for 35 years, shared a lesson passed on by his own mentor many years ago about the indescribable thrill that comes when a former student achieves a level of science that surpasses a faculty member’s.

“It’s so clear that’s exactly what’s happening here,” Ducey said.

When asked if there eventually could be human application for limb regeneration research, Duerr suggested it may not come in his lifetime, but that the recent research article brought the scientific community a step closer. He credited powerful technologies that are helping lead a revolution in biomedical research, allowing scientists to interrogate important questions on a single-cell level.

One thing that Duerr could confirm: he considers the recent publication to be the prize work of his academic career to date, the reward for many years of hard work.

“It was a big one,” he said. “But it was worth every second of it.”